Research - Field Experience - Projects

From salamander genetics, endangered bird monitoring, to the conservation of North America’s largest rattlesnake, my undergraduate, post graduate, and independent research experiences have varied widely. While reflecting on my experiences a common theme arose, the need for the work that I do to have real world, tangible conservation implications.

Orianne Society Herpetological Conservation: 2020

The Orianne Society focuses on the conservation of rare herps in the Southeast, specifically the conservation of the Federally Endangered Eastern Indigo Snake. During my time as a research technician with the Orianne Society I completed occupancy surveys of this imperiled reptile, along with surveys for Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnakes, radio telemetry of Spotted Turtles, and trapping for Suwannee Alligator Snapping Turtles.

The research that the Orianne Society conducts on these rare species is at the forefront of their conservation, informing management decisions and species status assessments.

Federally Endangered Saint Francis Satyr Conservation: 2020

The Saint Francis Satyr (SFS), a small, brown, Federally Endangered butterfly, is found no where else in the world but Fort Bragg Military Instillation in North Carolina. While working with the Haddad Lab, I conducted field surveys of the SFS, captive reared butterflies, and completed extensive habitat restoration of the wetland environments these butterflies require.

We were also able to breed SFS in captivity, and conducted releases of the butterflies to a new site on Fort Bragg that is now the most productive site for the butterflies on the base. Efforts to conserve this species are ever changing, ongoing, and challenging in the face of climate change, but the Haddad Lab’s dedication to this species is what keeps it hanging in the balance.

Appalachian State students protesting the lack of climate change mitigation.

Ecological Grief in an Educational Context: 2019

The Earth’s ecosystems are being altered at rates higher than any time in human history. Climate change, habitat destruction, and countless other ecological crises threaten ecosystems around the world. Impacts of these environmental issues have been shown to cause psychological consequences like anxiety, depression and PTSD (Clayton et al. 2017). These phenomena have been termed “Eco-anxiety”, “Eco-depression” and, “Eco-grief” and are considered psycoterratic issues, physiological issues tied to environmental change both directly experienced and perceived (Albrecht G. 2011). Scientists working on the front lines of conservation are often met head on with the consequences of ecological destruction and the psychological impacts of witnessing ecological destruction have not gone unnoticed. Gordon et al. 2019 suggests that the emotional trauma experienced by environmental scientists must be addressed with the same urgency and resources as other professions where trauma is common like paramedics, military, and law enforcement. Though, the scientific community often falls short of addressing mental health issues and providing resources for scientists navigating eco-grief. So where does that leave students training to pursue work in the conservation field and experiencing their first tastes of conservation work in the Anthropocene? I am currently working in a collaborative effort with Dr. Khadija Fouad to attempt to quantify ecological grief within Appalachian State’s learning environment.

Non-consumptive effects of aquatic invertebrate predators on Rana sylvatica tadpole behavior: 2019

The presence of predators has been shown to impact community structure of many different ecosystems. The impacts of predator presence on prey can be categorized as consumptive effects, the direct predation of lower trophic levels, and non-consumptive effects, the behavioral changes of prey due to predator presence. These non-consumptive effects can include the reduction of time spent foraging by the prey. In order to investigate if the presence of aquatic invertebrate predators impacts Rana sylvatica tadpole behavior, we performed a microcosm experiment using different caged predators and Rana sylvatica tadpoles. We measured activity and survivorship of the tadpoles by scan sampling over 24 hours. In the future, we hope to expand this research to consider potential behavioral differences between Southern Appalachian populations and SubArctic populations of Rana sylvatica tadpoles.

Woodfrog eggs to be used for our tadpole behavioral experiment.

Sampling for MeHg in a wetland in Churchill.

Investigation of Environmental Mercury in Wetland Communities in the Subarctic: Summer 2019

During summer 2019, I spent 8 weeks at Churchill Northern Studies Centre in the Subarctic as an undergraduate researcher for the Davenport Lab. During my time in Churchill, I worked to measure the amount of methylmercury (MeHg) in the local ecosystem. This research is important because MeHg is a potent neurotoxin that is known to cause developmental issues in children, as well as neurological issues in adults. Humans are most often exposed to MeHg by the consumption of fish. MeHg makes its way up the food chain through a process called biomagnification. Elemental mercury in an ecosystem can be transformed to toxic MeHg by microorganisms. Small animals then consume plants like algae that have been exposed to MeHg, and some of it accumulates in their bodies. When those animals are eaten by predators, the MeHg then begins to accumulate in the predator, and the amount increases over time. This process is magnified up the food chain. MeHg biomagnification can have serious consequences for human health if fish with high levels of MeHg are ingested by humans, specifically by women of child bearing age.

Due to human induced climate change, the Arctic is warming at a rate twice that of the global average. Frozen in the Arctic permafrost is the largest pool of naturally occurring mercury on the planet, estimated to be larger than all the mercury that has currently been released by human activities like mining and the burning of fossil fuels combined. Melting permafrost could potentially release significant amounts of mercury into the Arctic ecosystem, where it could make its way up the food web to humans. There are currently limited records of mercury accumulation in the Subarctic region, so my study will be the first to measure baseline levels, so future research can track if there has been a change over time.

Amphibian Use of Restored Wetlands: 2018-2019

The world has lost 87% of wetlands since 1700, which has undoubtedly affected many wetland-dependent species. In response to wetland loss, restoration and construction of wetlands has been increasing, though little is known about how recently constructed wetlands are colonized and used by the animals that inhabit them. The salamander Siren intermedia or Lesser Siren, is a top vertebrate predator in many wetland ecosystems, and can colonize newly constructed wetlands via drainages and channels. The Davenport Lab monitored a population of Siren in a less than 5 year old restored wetland in Southeastern Missouri for 20 months. After joining the lab in Fall 2018, I helped interpret the data they collected to better understand the population of Siren that now inhabits the wetland. Overall, our study demonstrates that Siren will utilize newly constructed wetlands and populations have the potential to function similarly to natural wetland habitats. Wetland managers should consider these often densely populated predators during management decisions.

Siren intermedia in situ. Photo by Kenzi Stemp.

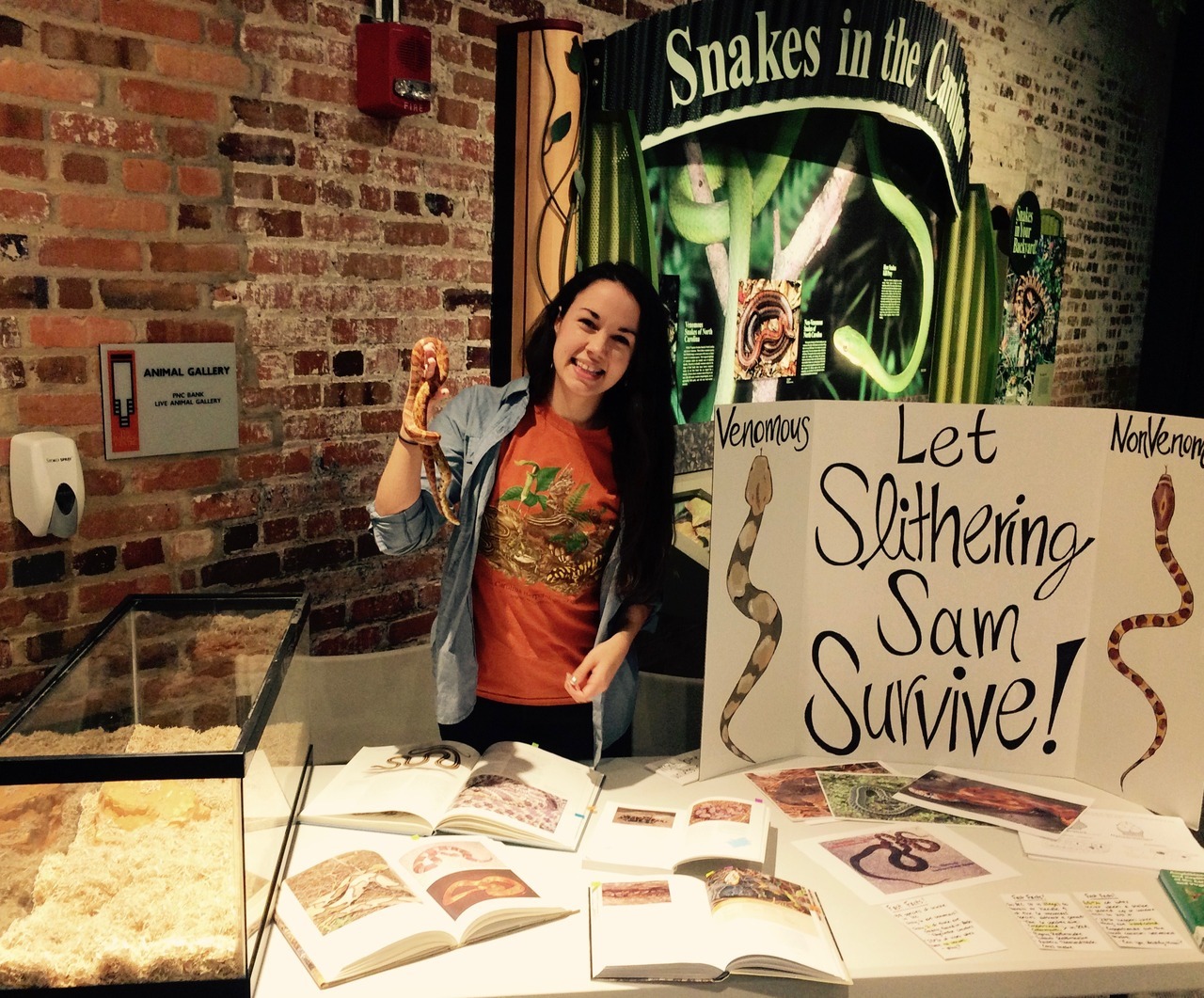

Environmental Education: 2017

When there’s no door, knock anyway.

Moving back home, I realized there was a lack of public environmental education in my area. I approached my city’s science museum and asked that they consider adding environmental programming to their First Friday events. They obliged! I began offering conservation based educational booths about North Carolina native reptiles and amphibians. Programming included venomous versus nonvenomous snake ID, how to help turtles cross the road (and to not keep them!), Neuse River Waterdog education, and much more! Sharing my love for the environment and the wonderful NC native animals we can find here was a gift to me personally, and I hope a gift for the children and their “grownups” I got to speak with.

Conversations on Conservation: Ethics and Issues of Bali Starling Rehabilitation on Nusa Penida: 2015-2016

Friends of the National Park Foundation is known internationally as the leader in Bali Starling “bottom-up” locally managed conservation. Their 2006 release of ~60 captive bred Critically Endangered Bali Starlings on Nusa Penida island, garnered attention from the likes of National Geographic, and Jane Goodall for its unique approach to conservation. There were reports of over 150 birds on the island by 2010. In 2015, I was grant funded by IAATE to perform an independent population survey of the Bali Starling on Nusa Penida. Instead of the claimed 150+ Bali Starlings, I found a struggling remnant of what the population once was, recently decimated by poaching. This study opened my eyes to the harsh realities of some conservation stories, and pushed me to question the very organizations that claim to be helping. Read my publication in IAATE’s The Flyer here.

Bali Starling, Nusa Penida Island.

Neuse River Waterdog. Photo by Jeff Hall of the Wildlife Resources Commission.

Neuse River Waterdog Watch: 2014

The Neuse River Waterdog, Necturus lewisi, is endemic to the water basin that flows through my hometown of Rocky Mount, NC, meaning it can be found nowhere else in the world! These aquatic salamanders are an “indicator species” meaning that their presence can indicate the quality of the body of water they are found in, and their absence can be cause for concern. The Neuse River Waterdog Watch was formed to advocate for the conservation of this species and develop a management plan to help save them. I aided the Neuse River Waterdog Watch in their water quality & Environmental DNA sampling, and habitat assessments of areas known to have these unique salamanders present.

Dusky Salamander Genetics and Hybridization: 2013-2014

How can two different species of salamanders, the Northern Dusky and the Mountain Dusky, look so different and yet share the same Mitochondrial DNA? After this genetic discovery was made in the Beamer lab, I performed a “sexual incompatibility” experiment to test if these species would potentially hybridize. My experiment had me keep 40 salamanders in my bedroom, switching them out in breeding trials. The experiment showed complete interspecific sexual isolation (no breeding across species), and was used in Dr. Beamer’s dissertation!

Northern Dusky, Desmognthus fuscus, top. Mountain Dusky, Desmognathus carolinensis, bottom.